|

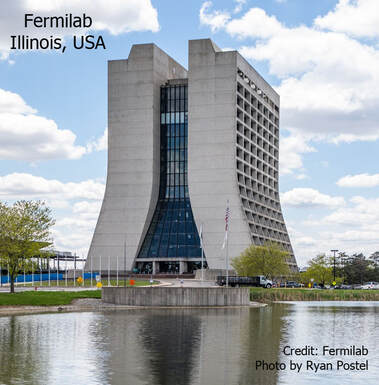

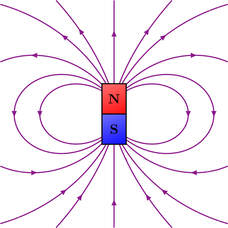

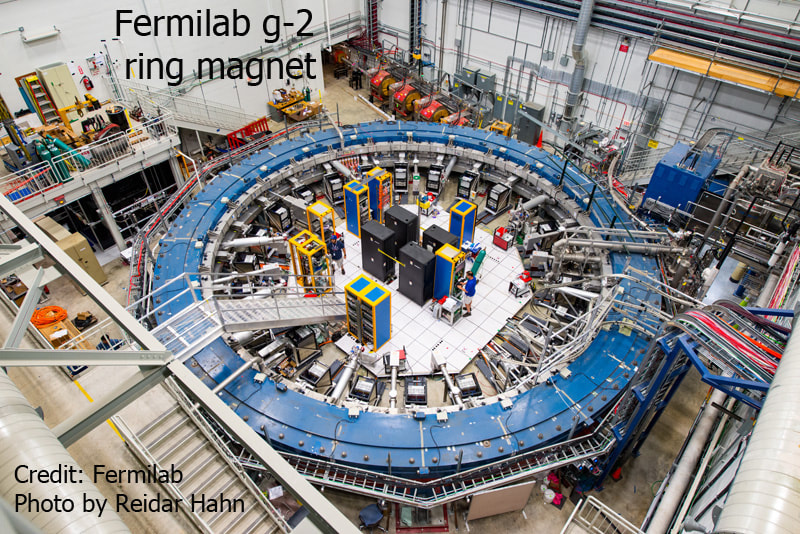

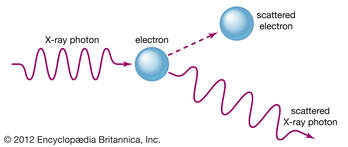

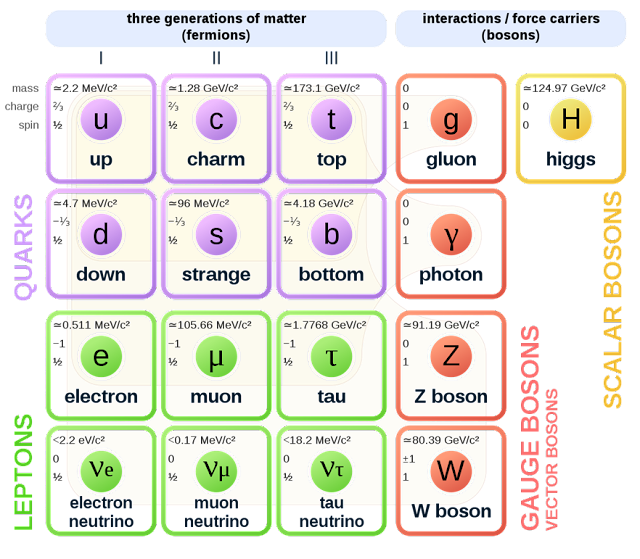

Graham writes … Welcome back to this topic, which we discussed back in October’s blog post. As always in physics and biology, significant developments always happen, which have distracted me from writing further about the prospect of new physics. It might be worth revisiting the October 2021 post to remind yourself briefly of some of the fundamentals that are relevant to today’s discussion.  As discussed then, one of the main theoretical pillars of the very small – the world of atoms and subatomic particles – is the standard model of particle physics. On the one hand, we know that the theory is ‘right’ in a very fundamental way, as we can perform detailed calculations to predict the results of experiments very accurately. This is evident from what we shall see later in this post. However, on the other hand, we also know that the standard model is not comprehensive. Again, as discussed in October, the theory of gravity (Einstein’s general theory of relativity) persistently ‘refuses’ to be unified with the standard model. Also, the mysterious ‘dark universe’ – dark matter and dark energy – which is believed to comprise about 95% of the matter/energy in the Universe is missing from the model. So, we know there’s lots to be done, but we really are not sure how to go about it. All we can do is attempt to find experimental results which are not in complete accord with the theory, and then probe what such an anomaly might mean for the model. The reason why I’m blogging today is to talk about a ‘strange’ experimental result, which has been reported recently by a team of scientists working at Fermilab near Chicago, Illinois. Given that this can be referred to as the ‘anomalous magnetic dipole moment of the muon’, or the ‘muon g-2 experiment’, we need to unpack some of the terminology to hopefully reveal something of what’s going on. So, where to start? Firstly, I’d like to look at a property of fundamental particles called spin. I think we are fairly familiar with the notion of spinning objects. If we spin up a macroscopic object, like a wheel, it acquires something called angular momentum, and the amount of angular momentum depends upon the mass of the object, how the mass is distributed and how fast it is rotating. It is the rotational equivalent of linear momentum. So, in the same way as we avoid standing in front of objects with large amounts of linear momentum, like a car travelling at speed, we also know intuitively not to tangle with an object with a significant amount of angular momentum, such as a large, rapidly rotating wheel. If we reached out and tried to grasp the wheel to slow it down, its significant rotational inertia will cause us grief.  Magnetic dipole field. Magnetic dipole field. However, scientists also talk about spin when referring to sub-atomic particles such as an electron, for example. However, the properties of the ‘spin’ of an electron are very different to that of a macroscopic body. For one thing the angular momentum is quantised in terms of magnitude and direction. Also, such particles are considered to be infinitesimally small point particles, and as such talking about physical rotation makes no sense. But intriguingly they do possess intrinsic attributes that are usually associated with the property of rotation. Such particles also possess a magnetic field very similar to that produced by a tiny, simple bar magnet. This type of field is referred to as a magnetic dipole field, with the usual so-called north and south poles. You may have seen the structure of this field in a simple school experiment by sprinkling iron filings onto a piece of paper which has been placed on a bar magnet. This type of magnetic field can be generated by the motion of an electric charge around a looped wire. So, we could imagine that electron is rotating, carrying its electric charge in a circular path around its axis of rotation, producing the magnetic field. However, we know that this cannot be so. If we were to envisage the electron as something other than a point particle, and try to use size estimates, its surface would have to be rotating faster than the speed of light to produce the measured dipole field strength! It’s clear that particle spin is a difficult concept for everyone (not just me!) to appreciate intuitively. So, after all that, what is the dipole moment? Well, if we place the electron in an external magnetic field, the north-south axis of the particle’s field will align with the direction of the external field, as a compass needle rotates to align with the Earth’s magnetic field to indicate north. Hence the electron’s field exercises a torque, or moment, on the particles magnetic axis to bring this alignment, and this is referred to as the dipole moment.  Another attribute of the particle which has its counterpart in macroscopic rotation is precession. If you think of a toy gyro and spin it up, then the force of gravity produces a torque which causes the axis of rotation to precess (or ‘wobble’), as illustrated in (the first half of) a video demonstration, which can be seen by clicking here. In a similar way, the magnetic axis of a particle (indicated by the the black arrow in the diagram) will also precess if placed in an external, uniform magnetic field (indicated by the green arrow). This is referred to as Larmor precession, after Joseph Larmor (1857-1942). I don’t know if you are still with me, but let’s come back to the media assertions about new physics, and the Fermilab announcement which mentions something called the ‘g-2 experiment’. The g here is referred to as the ‘g-factor’, which is a dimensionless quantity (a pure number) related to the strength of a particle’s dipole moment and its rate of Larmor precession. For an isolated electron, g = 2 according to Paul Dirac’s theory of relativistic quantum mechanics (QM), which he published in 1928. Subsequently, this theory has been superseded by the development of quantum electrodynamics (QED), which describes how light and matter interact. Using QED, we can perform the calculation for an electron that is not ‘isolated’. The g-factor calculation is not just about the interaction of the electron with the applied external magnetic field, but it is also influenced by interactions with other particles. This introduces another piece of quantum world terminology called quantum foam. This is the quantum fluctuation of the spacetime ‘vacuum’ on very small scales. Matter and antimatter particles are constantly popping into and out of existence so that the quantum vacuum is not a vacuum at all. For those of you with a bit of QM background, this is due to the time/energy version of the uncertainty principle. This idea was originally proposed by John Wheeler in 1955. Consequently, the electron also interacts with the quantum foam particles, and the influence of these short-lived particles affect the value of the g-factor, by causing the particle’s precession to speed up or slow down very slightly. The experimental value of the electron g factor has been determined as g = 2.002 319 304 362 56(35) where the part in brackets is the error. The theoretical value of g-2 matches the experimental value to 10 significant figures, making it the most accurate prediction in all of science.  The muon is 207 times more massive than the electron. The muon is 207 times more massive than the electron. So, we find that the behaviour of an electron conforms with theory very well, but what about other particles? The recent Fermilab experiment refers to similar work looking at a particle called a muon. So, what is this? The muon is a particle which has the same properties as an electron, in terms of charge and spin, but is 207 time more massive (see the blog post for October again, for details). It is also unstable, with a typical lifetime of about 2 microseconds (2 millionth of a second), but this is still long enough for the scientists to work with them. What the Fermilab team did was measure the muon’s g-factor in the same way that we have described for the electron. This time a difference between experiment and theory was observed, g(theory) = 2.002 331 83620(86), g(experiment) = 2.002 331 84121(82). Of course, the difference is tiny, so why the big deal? Well, the theoretical value describing how the quantum foam influences the value has been determined using our current model of the subatomic world – that is, the particles and forces as described by the standard model of particle physics. The fact that the experimental value differs suggests that there may be new particles and/or forces that are currently absent from our understanding of the quantum world. Another question posed by this result is why does the electron conform and the muon not? In the theory, the degree to which particles are influenced by the quantum foam is proportional to the square of their mass. Since the muon is about 200 times heavier than the electron, it is approximately 40,000 times more sensitive to the effects of these spacetime fluctuations.  At the end of the day, do the Fermilab results have the status of a confirmed, water-tight discovery? Well, actually no. The degree of certainty at present is at the 4.2 sigma level, which suggests that there is a roughly one chance in 100,000 that the result could be a result of random chance. To get the champagne glasses out, and to start handing out Nobel prizes, further work is required to achieve a 5 sigma result (again see October’s post). So, where does all this take us? The bottom line is that it tells us there are things about the quantum world that we don’t know – which, you could say, we knew already! But this is how physics works. To paraphrase Matt O’Dowd, Australian astrophysicist, “ … to find the way forward, we need to find loose threads in the [current] theories that might lead to deeper layers of physics. The g-2 experiment is just one loose thread that was begging to be tugged. The scientists at Fermilab have just tugged it hard …”. I await further developments! Graham Swinerd Southampton March 2022

0 Comments

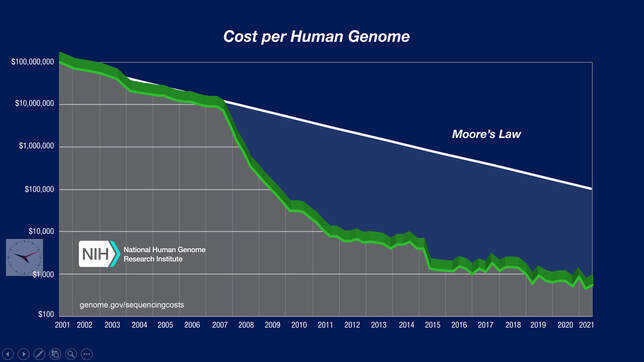

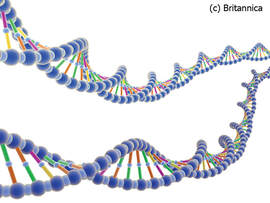

John writes … We, my co-author Graham Swinerd and I, have produced a vlog (video blog) focussing on my expertise – biology, and in particular what’s going on in the world of genetics. To see the video, please click here. What follows is a brief commentary on the video’s content. When I started my Natural Sciences degree I was fairly sure that I would come out the other end as a functional ecologist – someone who studies ecology with an emphasis on plant and animal adaptive mechanisms. How wrong I was. During those three years I became completely hooked on the molecular aspects of genetics and on biochemistry and so it was a natural progression that for my PhD I studied DNA biochemistry (in the context of plant cell division).  It was an opportune time to become involved in that area of science. The ‘golden age’ of genetics was about to dawn. The basic mechanisms involved in the working of DNA and genes were known and there was already some information on control mechanisms, an area that I hoped to eventually get involved in. And then came the invention of genetic engineering techniques (and associated spin-offs) which, as I say in the video, gave us a huge range of research possibilities. It opened up previously impossible (and some cases undreamed of) lines of investigation. Combining our knowledge gained by these new techniques with our knowledge of biochemistry led to DNA sequencing; detailed analysis of individual genes gave ideas about gene control mechanisms, ideas that could be tested with techniques based on genetic engineering. More recently, invention of new methods for DNA sequencing have very significantly reduced the cost and the time involved in analysing any DNA sample of interest, including whole genomes from individual members of a species (rather than an ‘average’ genome for that species). The applications of this are very widespread, as I mention briefly in the video. And now another technique has entered our tool-kit, namely genome editing* which enables us to knock out specific genes in a highly targeted manner, again as described in the video. But I need to say one more thing: the more that I know about DNA and genes and the ways in which they work, the more awestruck I become. In my own specific area of research, the beauty and complexity of the mechanisms that a cell uses to control DNA replication are amazing. The psalmist was in awe of the God who made the ‘heavens’ (Psalms 8 and 19) but I am equally in awe of the God of our genes. * For those who want to know a bit more about genome editing, I have included two papers. One is the uncorrected proof of an article in Biological Sciences Review and the other, at a higher level of understanding, was published in Emerging Topics in Life Science. Please click on the files below to download the files. John Bryant Topsham, Devon February 2022

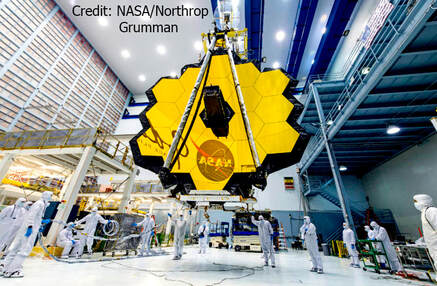

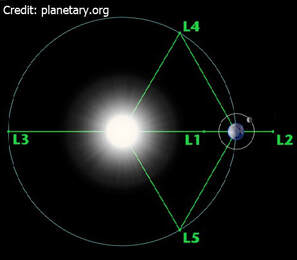

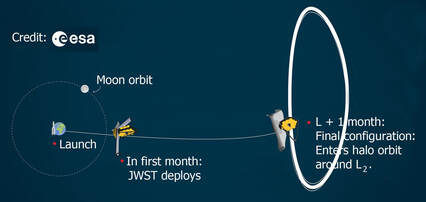

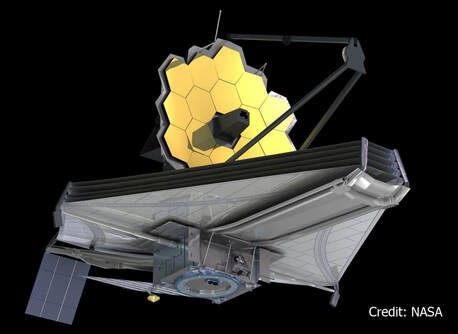

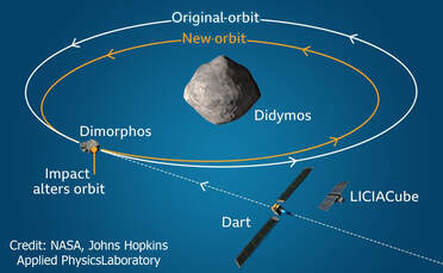

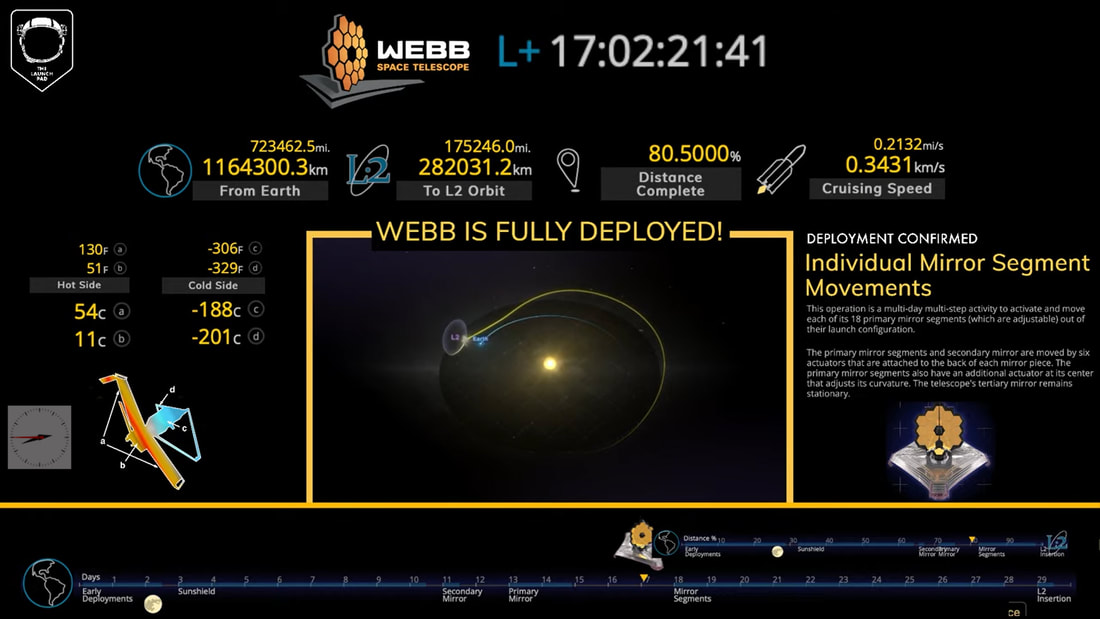

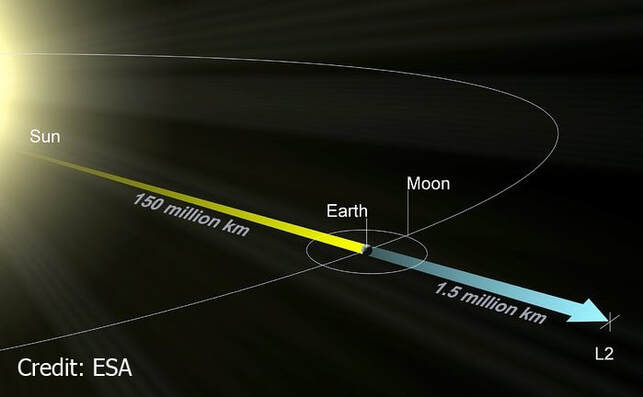

Graham writes … A new age of astronomy is about to begin, with the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). The new space observatory, named after the NASA administrator during the Apollo era, lifted off at 12.20 UT on Christmas Day 2021 atop a European Ariane 5 heavy-lift launch vehicle. A video of the launch and ascent (simulated) can be seen here, and another of the separation from the launch vehicle and power array deployment can be seen here. Both these videos are courtesy of Arianespace/NASA. Apologies once again to those of you who are looking out for the ‘New Physics? Part 2’ blog post, but the launch of the JWST is long-awaited and cannot be overlooked. If the new space telescope works as it supposed to, then it will most likely make history as did its predecessor, the iconic Hubble Space Telescope. This is a truly monumental event for the astronomy and cosmology communities.  At the time of writing, 6 January 2022 (~ launch + 12 days), the JWST is still on its way to its operational location – the Earth-Sun Lagrange point L2, which is about 1.5 million kilometres from Earth. It also has to deploy a significant number of mechanisms during its journey, so there are an awful lot of crossed fingers in the control centre and around the world. The operational configuration has a 6.5 metre aperture telescope and a sun shield about the size of a tennis court (~ 22 m x 12 m), and all this had to be stowed inside the launcher fairing of the Ariane 5. Consequently, there are around 140 release mechanisms that must perform perfectly to shape the final operational telescope. All this is going on while the JWST is in transit to L2, which will take about 30 days. An excellent video of the complete deployment process during the transfer, courtesy of NASA/Northrop Grumman, can be seen here. Once it arrives at the Lagrange point, it will enter its operational orbit, called a ‘halo orbit’, around this location. For more details about this exotic orbit and Lagrange points, see (1).  So, briefly, what is a Lagrange point and why is L2 a good place to operate an astronomical telescope? In any three-body system (for example, in this case, the Earth, Sun and spacecraft) there are in fact 5 Lagrange points, named in honour of the Italian-French mathematician Joseph Lagrange. The second Lagrange point L2 is about 1.5 million kilometres beyond the Earth’s orbit around the Sun (on a line joining the Sun, Earth and spacecraft) where the gravitational and rotational forces cancel to produce a place of equilibrium where the space observatory can be ‘parked’. This an ideal place for a space telescope, as the Earth only subtends an angle of about 0.5 degrees, so the sky viewing efficiency is excellent. The downside of this choice of orbit is that the observatory cannot be visited by astronauts to perform repairs or servicing. You may be aware that the Hubble Space Telescope was visited on five occasions by astronauts, as it was accessible in a low orbit near Earth. The table gives an outline of the main attributes of the observatory. Table: Summary of spacecraft characteristics Launch mass: 6,200 kg Overall dimensions: 22 m x 12 m (sun shield) Mirror aperture: 6.5 m (compared to 2.4 m for the HST) Maximum electrical power: 2 kW Planned operational lifetime: 5 to 10 years Operational temperature: -230 degrees (on the dark side of the sun shield)  Towards the end of this month (January 2022), the observatory should have completed the sequence of deployment mechanisms, and will enter its operational ‘halo orbit’ around L2 in its final configuration. While on station the sun shield will be directed towards the Sun and the subsystem module will be permanently located on the sunny side of the shield. This will enable the supporting subsystem elements, such as power, data handling and communications, to remain at a sensible temperature to ensure reliable operation. The telescope and associated payload elements will reside permanently on the dark side of the shield so that its temperature will be very low (see the last entry in the table). This thermal constraint indicates that the telescope is optimised to operate in the infrared (IR) part of the electromagnetic spectrum – that is, heat radiation (more about this below). The telescope needs to be at a very low temperature so that its own IR emissions do not interfere with the IR observations. The telescope’s mirror is comprised of 18 hexagonal elements manufactured from beryllium, with a thin coating of gold deposited on the reflective surface. This striking feature of a gold mirror is that it helps improve the mirror’s reflection of IR light. The composite hexagonal pattern of the main mirror has become something of a logo for the JWST project.  So why the emphasis on IR optimisation? This is, of course related to the science objectives of the observatory. It is hoped that the JWST will be able to see the ‘first light’ in the Universe, about 600 million years after the Big Bang, when the swirling dark clouds of hydrogen and helium began collapsing to form the first stars. It is also hoped that the processes involved in the origin of galaxies will be revealed. The ultra-violet and visible light emitted by the first luminous objects in the Universe is significantly red-shifted, due to cosmic expansion, into the IR part of the spectrum. Another objective is to study the birth of stars more locally, and the formation of embryonic planetary systems, which are usually obscured by the debris and dust associated with these events. Short wavelength visible light is appreciably scattered by dust. However, the longer wavelength IR radiation is less affected by this, allowing the telescope to observe these formative episodes.  Needless to say I am very excited by the prospect of all this, but we will have to wait till summer 2022 to see the first output from the JWST. Meanwhile, there is an awful lot of critical moments in the deployment and commissioning of the observatory. I am keeping everything crossed that this ambitious programme will all work out just fine! Graham Swinerd Southampton January 2022 (1) Graham Swinerd, How Spacecraft Fly, Springer, 2008, pp. 83-89. Graham writes … John and I are offering an additional post in recognition of NASA’s DART mission, which launched recently (24 November 2021). The acronym DART stands for Double Asteroid Redirection Test for reasons which will become apparent. The objective is to crash the spacecraft into a small asteroid to determine the effect the impact has upon the orbit of the asteroid. If all goes well, the impact will occur on 26 September 2022.  So why is NASA deliberately crashing its valuable spacecraft into a lump of rock? The answer to this question goes back some 60 million years, when an asteroid about 10 km across impacted what is now called Central America, creating a global catastrophe which ultimately led to the extinction of the dinosaurs. The impact speed of the object is unknown, but most likely of the order of 10s of kilometres per second, resulting in a hugely energetic event which dwarfs those created by our most powerful nuclear weapons. We discuss this event, and its consequences, in the concluding section of Chapter 5 of the book.  Coming back to the twenty first century, we consider the occurrence of such an event to be very unlikely. However, we also appreciate from consideration of Earth’s history that such catastrophes are inevitable in the future. For example, the 1.1 km diameter Barringer Crater in Arizona, USA was created by the ground impact of a 50 metre diameter asteroid some 50,000 years ago. Also, an air burst of an asteroid in the Tunguska region of Siberia in 1908 flattened forestation over an area about the size of the London M25 orbital motorway. This one was caused by an object about 60 metres across. Clearly, we have to wait a very long time for a 10 km impactor, but the arrival of these smaller objects occurs more frequently, and the devastation that would result if one struck a large city cannot even be imagined. So, we need to take planetary defence, with regard to celestial impactors, seriously. This is why the DART mission was proposed and implemented. The spacecraft is referred to as a ‘kinetic impactor’, and you could say that the process is a bit like a game of celestial billiards. When the spacecraft hits the asteroid, it will change the asteroid’s speed a little, and this small change will alter the asteroid’s orbit. It is effectively a test to see if the orbit of an asteroid, that threatens to impact the Earth in the future, can be changed sufficiently to prevent a catastrophic collision with Earth.

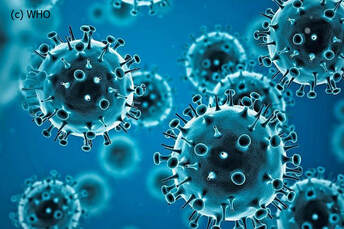

The target asteroid for the test is a 160 metre diameter object called Dimorphos, which itself is in orbit around a larger asteroid (780 metres across) called Didymos – see images. To discuss asteroid impacts in general, and the DART mission in particular, John and I have attempted a ‘vlog’ – that is a video blog which we have posted on YouTube. If you would like to see this please click here. We have not used this medium before, but nevertheless we hope you find it interesting. Please leave thoughts and comments on this website, or on YouTube. Graham Swinerd Southampton December 2021  Francis Collins, a very distinguished medical geneticist, well-known for his Christian faith, has just retired from heading the USA's National Institutes of Health. He was appointed to the post 12 years ago by President Obama and has now reflected on his time at NIH and on related issues, in an interview published in the scientific journal Nature, which can found here. Some of our readers may also be interested in Collins' own book (Francis S. Collins, The Language of God, Simon & Schuster, 2007). This is one of Graham’s favourite books, helping him to get to grips with aspects of the biology of life, which don’t come easy to a physicist. Graham Swinerd and John Bryant December 2021 My friend Anthony Wilson, poet and educator, has published several ‘thin volumes’ of his own wonderful poems and has also produced a beautiful and wide-ranging anthology of other poets’ work, entitled ‘Lifesaving Poems’ (Bloodaxe Books, 2015). In his commentary on Tides, a poem by Hugo Williams, Anthony alludes to the words of Seamus Heaney who became conscious in his late 40s of his need to ‘credit marvels,’ or in the words of another commentator, John Wilson Foster, to nurture ‘a more conscious receptivity to the wondrous inherent in the commonplace’. This is a theme that emerges in Chapter 5 of our book. There I suggested that our familiarity with the mechanisms involved in the working of genes has meant that those mechanisms seem ‘ordinary’ or even commonplace. Indeed, in some ways they are, taking place during every second of every day in every living cell. And yet, if we look beyond that familiarity, that ordinariness, that commonplaceness, they are indeed marvels.  We can see the same sequence of thoughts when we consider how some of the findings of science are used to benefit human society. The announcement that ‘scientists are now able to …’ (fill in your own favourite here) induces our amazement, our wonder but those emotions fade as the particular innovation becomes embedded in medicine/agriculture/IT etc. And thus it has been with PCR – a three-letter abbreviation that has become very familiar to us during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, for many people, that’s where their knowledge of the process stops, i.e., it’s a method used to test for the presence of the virus but there’s no need to know any more than that. However, I want to say more than that because it is a beautiful example of how the knowledge revealed by scientific research (or, as tabloid newspapers might say – the work of back-room boffins) can be put to a use that benefits society. PCR stands for Polymerase Chain Reaction and those words sum up beautifully the essentials of the process. Let’s start at the beginning. A polymerase is an enzyme (a biochemical catalyst) that makes polymers – molecules built up from many similar smaller molecules. As we describe in Chapter 5, DNA is a polymer and the individual units of which it is made are called bases (1). Enzymes that build DNA are called DNA polymerases (2). The American biochemist Kary Mullis proposed that the stable DNA polymerases from certain heat-tolerant bacteria could be used in a ‘chain reaction’ to amplify (make many copies of) pieces of DNA (3). He successfully demonstrated the technique in December 1985 and it quickly became embedded as a routine tool in molecular biology. Mullis shared the 1993 Nobel Prize for Chemistry in recognition of the importance of this.  Further, we can, in any sample of DNA, direct the reaction so that it only copies the segments that we want to be copied. The detail is not important except to say that this is achieved by use of primer molecules that can be synthesised in the lab to recognise particular DNA sequences. PCR will then amplify the tract of DNA between the two primers. We can build up a stock of any gene or other DNA sequence in which we are interested. Further, as I am sure dear reader you will have realised, if the sequences at which the primers are aimed are not actually present in our DNA sample, then no amplification occurs. The importance of this is immediately apparent when we apply the technique to the detection or otherwise of, for example virus genes (more about this later in this blog).  As mentioned above, it did not take long for PCR to become established as a routine tool in labs working on genes, including my own at the University of Exeter. Prior to the technique’s invention, amplification of particular genes or other sequences was done by growing them in bacteria by a process called molecular cloning. It was certainly more cumbersome and time-consuming than PCR and it was often difficult to clone just the piece of DNA in which one was interested. The small machines (with a footprint smaller than a piece of A4 paper) in which PCR is carried out became part of the standard kit in any molecular biology or molecular genetics lab. The wondrous had become commonplace. At this point a quick reminder of basic mechanisms involved in the way that genes work will help to understand how PCR has been used during the pandemic. When a gene is working, it is not the code in the DNA itself that is read but the code in a copy of that gene. That copy is not made of DNA but of RNA and is known as messenger RNA (mRNA), as described more fully in Chapter 5. However, some viruses, including SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) use RNA as their genetic material. It is the genes themselves that act as mRNA, without the need to copy from a DNA template (4) and the unsuspecting host cells use that virus mRNA to make components of the virus. If you have followed this discussion so far, you can see that this might be a problem for PCR, which amplifies DNA, not RNA. Once again however, scientific discoveries come to our rescue. There are some viruses whose ‘life-style’ involves copying RNA into DNA. These include HIV and, in the plant world, cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV). And of course, there is an enzyme (biochemical catalyst) that does this. It is called reverse transcriptase (RT), a DNA polymerase that makes DNA copies of RNA molecules (5). When we use it in the lab we can again employ specific primers (see above) so that only the RNA of interest is copied. This can then be amplified by conventional PCR which, by using careful changes of conditions, takes place in the same tiny test tube as the RT reaction. Virus RNA (or a specific section of virus RNA) is copied into DNA with RT; DNA is amplified by PCR.

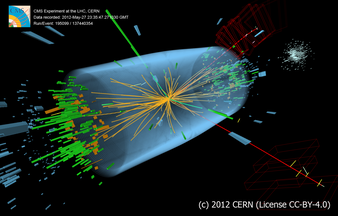

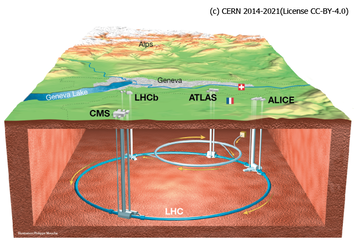

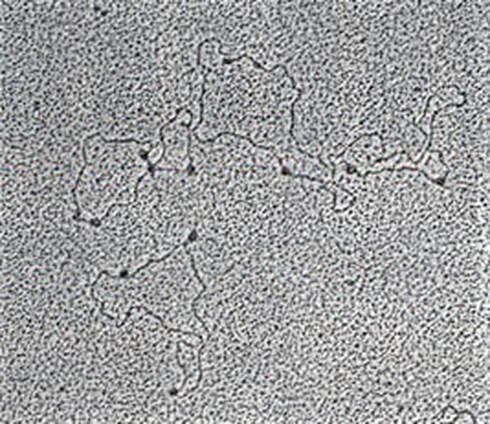

In testing for SARS-Cov-2, a standard is included to make sure the technique is working and the technician will look to see whether or not there has been any amplification of virus-specific sequences. A lack of amplified viral sequences indicates an absence of virus in the original sample, i.e., a negative test result. There are different ways of detecting the amplified DNA. In one method, fluorescent DNA-binding chemicals are used and in larger, more sophisticated PCR machines than the basic machines I mentioned earlier, the detection of the fluorescence can be done in situ as the reaction proceeds. With suitable calibration with appropriate standards, the amount of fluorescence can be related to the amount of RNA in the original sample. In other words, the process can be quantitative – hence the shorthand name for the overall procedure is qRT-PCR. In my lab for example, we used this procedure to compare the amounts of mRNA from two different genes in dividing plant cells (6). So, if my descriptions have been clear enough – and I hope that they have – next time you hear about a PCR test for presence versus absence of SARS-Cov-2, I hope you’ll think about Seamus Heaney looking to ‘credit marvels’ in the commonplace. I hope you’ll remember the skill and inventiveness of Kary Mullis and of the scientists who subsequently tweaked his PCR technique. I hope that you will see the marvels in the ‘commonplace’ but nevertheless beautiful biochemical reactions, reactions that are going on all around us – and indeed within us – that are employed in the PCR procedures. I hope you will see the ‘poetry of nature’ in those reactions. And dare I hope that you’ll also thank God for science? John Bryant Topsham, Devon November 2021 (1) Technically, the building blocks are actually deoxyribonucleotides; a base is part of a deoxyribonucleotide (or, in RNA, part of a ribonucleotide). (2) These are enzymes with which I and my research team are very familiar: e.g., https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/43.1.31 (3) When working optimally, the process can generate a billion copies from a single piece of DNA in just a few hours. (4) Tobacco mosaic virus (which also attacks tomato plants) also has an RNA genome which acts directly as mRNA (or in technical terms, is a + stranded RNA virus). It was widely used in research as a ‘model’ for viruses of this type, including our studies of how the viral genome is copied: https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a086791, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a086933 (5) It was a privilege for me to be part of the group that discovered and started to characterise the CaMV reverse transcriptase https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/13.12.4557 (6) https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erg079  Graham writes … For those of you who are into this kind of thing, there have been rumours in the scientific press recently that new physics is afoot. So, what’s it all about, and should we be excited? I know I will be … But before we talk about the latest developments … the last time that there was a significant engagement between the physics community and the popular press was in 2012, when the discovery of the Higgs boson was confirmed. Looking back on it, it was quite an exciting time. Interest, and confusion, was whipped up by the adoption of an unusual nickname for this elusive sub-atomic particle – the ‘God particle’! This was principally the reason for the media interest, and this unlikely title was first coined by Physics Nobel Laureate Leon Lederman in 1994. He told people that he invented the name because the Higgs boson – then a purely theoretical entity – was ‘so central to the state of physics today, so crucial to our understanding of the structure of matter, yet so elusive’ (1). As it turned out, this rather confusing association of the particle with God turned out to be not such a bad thing, as it got people talking about frontier research in particle physics. I recall a time in the 1960s/1970s when particle physics was in a state of confusion, with the discovery of a plethora of new particles, but without any understanding of the underlying structure of how they fitted together. Over time, as mentioned in Chapter 2 of the book (2), the physicists have developed a ‘Standard Model of Particle Physics’ that hopefully makes sense of it all. This has been a great success, and has allowed a greater understanding of the quantum world. The diagram below shows the current status of the standard model, indicating all the particles that are believed to be fundamental (each of the particles also have a corresponding antiparticle, which are not shown). In other words, the particles listed are considered to be indivisible. For example, the ‘familiar’ particles that make up the nucleus of an atom – the proton and the neutron – are now known to be divisible. These particles are composed of 3 quarks, (the family of quarks is shown in purple). In this case, the proton is made up of 2 ‘up’ quarks and one ‘down’ quark, and the neutron 2 downs and one up. There are six ‘flavours’ of quark in all. Shown in green, there are six types of particle referred to as leptons – after the Greek leptos, meaning ‘lightweight’ – which are also considered to be fundamental. The most ‘familiar’ of these is the electron. However, this has larger counterparts – the muon and the tauon, which are about 200 times and 3,500 times heavier than the electron, respectively. Associated with each of these, there is a neutrino particle. Remarkably, physicists have not yet been able to measure the fundamental attributes of the neutrinos (such as mass!) because their interaction with matter is so extremely weak. For example, they can pass through our home planet without leaving any tell-tale sign of their presence. All that is known is that the three types of neutrino have a combined mass that is several million times less than that of an electron, but there is sufficient understanding of neutrino behaviour to appreciate that they are not massless.  The red particles are called bosons and have the property of being ‘force carriers’, and have the job of exercising the forces between particles. For example, the electromagnetic (EM) force acts upon charged particles by the exchange of a photon. A similar mechanism is envisaged for the gluon which governs the strong nuclear force, and the W and Z bosons which administer the weak nuclear force.  However, I am aware that our understanding of the quantum world remains incomplete. For example, it is worth remarking upon the significant absence of a boson (‘force carrier’) for the gravitational force (in its absence, it has nevertheless been given the name ‘graviton’). As discussed in the book (3) gravity has evaded all attempts to include it in the standard model. Indeed, there is debate as to whether gravity is a force in the same sense as the other three fundamental forces (EM, weak nuclear and strong nuclear), and this is probably an obstacle to achieving the unification. As described in the book (4), the mechanism through which Einstein’s gravity acts is completely different to those of the other forces. Briefly, a mass (for example, a star) produces a curvature in the surrounding space-time, and objects moving in the star’s neighbourhood move along trajectories that take the shortest distance in the curved geometry. So, it could be summarised by saying that mass shows space how to curve and curved space shows mass how to move. Inherently Einstein’s gravity is a classical theory, involving ‘geodesics in a curved Riemannian geometry’ (this phrase may be meaningful to some readers?), so it is not too surprising that the quest for unification with the other ‘quantised forces’ is proving to be very challenging. It is a problem of attempting to unify an inherently classical theory with its quantum counterparts.  Another rather large hole in the standard model is the notion that so-called ‘normal matter’, as described by the current standard model, comprises only about 5% of the total matter/energy content of the Universe. The other 95% is comprised of dark matter and dark energy (5), and currently we have no idea what these are. So, there is probably a whole new family of particles waiting to be added to the standard model to describe this so-called ‘dark universe’. We know our theories are incomplete, and there is plenty of new physics waiting for a team of new ‘Einsteins’ to show us the way.  However, coming back to the things we think we understand about the standard model, we finally come to the Higgs boson, identified in yellow and sitting all by itself on the right-hand side of the diagram. So, what is the Higgs boson, and what does it do? It all started with some published theoretical work by Peter Higgs in 1964, which first predicted the existence of the particle. It took a remarkable 48 years for the experimental community to catch up with the theoreticians, with the development of the Large Hadron Collider facility at CERN (Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire) near Geneva. This remarkable machine produces sufficient energy to allow the creation and detection of this new particle, for which Peter Higgs, now a retired professor at the University of Edinburgh, UK, received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2013. In order for such a breakthrough to be declared officially as a discovery, it has to be confirmed at the ‘5-sigma level’. A 5-sigma result is considered to be the gold standard for significance, which is just a bit of statistics jargon which translates into a tiny probability (1 chance in about 3.5 million) that the event is a random fluke. The remarkable property of the Higgs boson is that it gives all the other particles in the standard model the attribute of mass, with the accompanying property of inertia. The Higgs boson has an associated field which has a non-zero value throughout all of space, which is sometimes referred to as the Higgs ocean. As particles traverse this field, they interact with it in proportion to their mass – in other words, each fundamental particle acquires its specific mass. Of course, some particles such as photons of light are massless, because they do not interact with the Higgs field at all. More recently, physicists have continued to uncover further anomalies that point to new particles that comprise quantum reality. I hope you will join me again when I say something more about this intriguing idea in Part 2 of ‘New Physics?’. Graham Swinerd Southampton October 2021 (1) Alister McGrath, Inventing the Universe, Hodder & Stoughton, p. 57. (2) Graham Swinerd & John Bryant, From the Big Bang to Biology: where is God?, KDP publishing, 2020. (3) Ibid., chapter 2, pp. 36-38. (4) Ibid., chapter 3, pp. 52-56. (5) Ibid., chapter 3, pp. 74-76. John writes ...  I have worked directly or indirectly on DNA and genes from my PhD student days and throughout my research career. My focus was at the interface of biochemistry and genetics, an area of science that we call Molecular Biology and with which I am very familiar. It is replete with marvellous molecules and mechanisms, although, for those of us who are practitioners, it is too easy to take those marvels for granted. We need to ‘stand and stare’ perhaps for just a few minutes to remind ourselves that the whole topic is amazing. Let me start with the genetic material itself, DNA. DNA molecules are not really complex, although they can be very long (long in relation the dimensions of living cells). DNA molecules are polymers, that is they are built of many individual components linked together. These individual components are called bases in biochemical shorthand and there are only four sorts – as I said, DNA is not a complex molecule – and they can occur in any order. This simplicity fooled scientists for a long time: how could such a simple molecule carry genetic information? DNA was discovered in 1869 and was shown to be present in chromosomes early in the 20th century but it was not until the end of World War II that this key role of DNA was finally demonstrated beyond doubt. And of course, that demonstration led to extensive further research, including the elucidation of its structure by Watson and Crick – and others – in 1953. All the information required for the development and second-by-second life of all organisms is encoded just in the four bases of DNA, the specific information coming from the order and the number of bases in subsections of DNA molecules that we call genes. Further – and this fact still fills me with amazement – all living organisms on Earth read the code in the same way. Every living organism is related to every other, consistent with the idea that there was just one origin of life (abiogenesis) and all life-forms are derived from that common beginning. Caption for image: In bacteria, the DNA molecules are circular and, in addition to their main DNA molecule, they often have mini-circles that carry just a few genes. We constructed artificial mini-circles by splicing different pieces of DNA together in order to study the interaction of a particular protein (see below) with particular structures in DNA. The interaction is seen here under an electron microscope. Image copyright © Sara Burton, John Bryant and Jack Van’t Hof.  But there is more. The information in DNA must be passed on. Every new cell needs a faithful copy of the genetic information from its ‘parent’. This is where the famous ‘double helix’ comes in (if you are not sure what a helix is, think of a ‘spiral’ staircase. A spiral staircase is actually not a spiral but a helix). A molecule of DNA consists of two helices wound round each other and which are held together because of specific abilities of the bases to form pairs with each other. Using just the initials of the bases to indicate their names, A in one helix can only pair with T in the other; similarly, G can only pair with C. I’m sure you can see that this immediately provides the means of passing on the code faithfully. If the two helices separate, then each single helix directs the synthesis of a new partner helix. For example, a T in the pre-existing single helix dictates that there must be an A at that position in the new helix. The structure of DNA means that it can direct its own faithful copying. That is both awesome and beautiful in its simplicity. If a human engineer had come up with this, we would say that he or she was a genius. As a Christian I say that the genius here is God. Thus the genetic code is safely passed on from generation to generation, but what does the code actually do? Well, it directs the synthesis of proteins, the cell’s working molecules. There are thousands of different sorts, many of which are enzymes – proteins that carry out biochemical reactions. Proteins are polymers (see above) built with amino acids, of which there are 20 types that vary significantly from each other in shape and size. The shape of a protein, essential for its function, depends on the particular array of amino acids – overall number and the order of different types within the molecule. Some proteins are small and quite simple, others are very large (in molecular terms). A code based on just four bases (read in groups of three) in DNA tells the cell the order in which to put the amino acids in a protein.

How does this happen? How is the code translated? The answer is not ‘Google Translate’ as one school student suggested to me! I’d like you to envisage the code as a row of beads of four different colours and the cell’s pool of amino acids as a pile of LEGO (TM) bricks of several different shapes and sizes. Those bricks do not fit onto the beads. In the same way, an individual amino acid cannot on its own recognise three bases and line up with them. The answer to this conundrum is in the form of adapter molecules which can recognise an individual amino acid and the three-base code that specifies that acid. These adaptor molecules ensure that the amino acids are built into proteins in the right order. It is an amazing mechanism and we have no understanding of how it evolved. This leads back to a point that I made at the beginning of this article. In Chapter 5 of the book, I wrote ‘… I cannot help think that we biologists are so used to this that we have become a little blasé.’ When we pause to think a little more deeply we can only react with awe and wonder at God’s magnificent creation. Note: I wrote a revised version of this blog for the Faraday Institute’s Faraday Churches web page. You can find it here, with a brief introductory paragraph from Ruth Bancewicz. John Bryant Topsham, Devon September 2021 Graham writes … Sometimes when John and I are leading a conference, we ask people to speculate about what is the most complex object we have discovered in the Universe. After a few responses, usually related to celestial objects, we guide the delegates by suggesting that there are many of these objects in the conference venue – the human brain! The working network of the brain has around 100 billion neurons (brain cells), resulting in the order of a million billion neuronal connections. In some way that science has yet to fully understand, this leads to mind and consciousness, as the mechanisms that give rise to these attributes remain a mystery. Given that mind and consciousness are the things that make us human, and are fundamental to our daily experience of ourselves and the world around us, it is remarkable that we have yet to comprehend how this works. One of the biggest scientific mysteries resides inside our head!  Earlier in the year I tuned in to an online meeting of Christians in Science to hear a talk called Am I just my Brain? by Dr Sharon Dirckx. As you may know by now, I am not exactly well-qualified to comprehend the subtleties of neuroscience, but I was delighted that the talk was pitched at my level, and I was also bowled over by what she had to say about our current understanding (or controversy) about ‘mind’. Dirckx (pronounced ‘Dirix’) is currently a Senior Tutor at OCCA (Oxford Centre for Christian Apologetics), after acquiring over a decade of hands-on experience in functional magnetic resonance imaging. Subsequently, I have acquired a copy of a neat little book that she has written with the same title (1). It was a good read, that I can recommend. This little book has much to say about a great many things, but I would like to say something about two topics in particular.  Firstly, that there is still debate about where the human mind ‘resides’. Given the importance of mind, I was really quite excited by the idea that the practitioners and philosophers are still discussing this issue. Afterall, I am effectively my mind. It is where I play out my inner life, it is where my memories reside (and effectively, my memories are what make me me) and it is where I organise and plan my life. The Oxford English Dictionary sums up ‘mind’ concisely as: The seat of awareness, thought, volition, feeling and memory. The debate about where exactly this seat resides has apparently gone on for a very long time, and still continues today. Having said this, it is fair to say that the scientific view is that the mind is the brain. All the complex facets of my inner life are just the firing of neurons, and the seat of mind is just brain chemistry. In this view, I am indeed just my brain. Another option is that the brain generates the mind. Once the brain reaches a certain level of complexity, mind emerges as something new and distinct, the word ‘distinct’ suggesting that the seat of the mind is controversially beyond the brain. In this scenario, given that mind is a product of brain, the mind ceases to exist once the brain dies. A third option offered by Dirckx is that mind is beyond the brain. Mind and brain are two distinct ‘substances’ that can interact, but they can also operate independently of each other. In this scenario, the brain can influence the mind, but the mind can also interact with the brain and the body – there is two-way traffic as, for example, when the body manifests psychosomatic illness. Clearly, this option is not recognised by the materialistic brand of science that pervades contemporary thinking on these things. Neuroscience can only recognise the first option.  The second topic is to do with whether, as human beings, we have free will – again a bone of contention for scientists and philosophers over many years. This discussion continues in the more contemporary setting of YouTube – you will find pages of responses if you just enter ‘free will’ into the search box. Why is this particularly of interest to Christian believers? It is a fundamental facet of the Christian faith that we are free to choose. God is not in the business of interfering with our free will. We can choose to go God’s way, or our own way – in other words we can choose to follow him. As God’s creations, he could have programmed us to follow and love him, but then the notion of love is meaningless in a world full of what effectively would be a population of programmed human ‘robots’. This is made clear by Jesus when he said “So I say to you: Ask and it will be given to you; seek and you will find; knock and the door will be opened to you.” (2) It is our choice whether or not to ask, seek or knock. However, there are many so-called ‘hard determinists’, who refute our ability to make free choices, despite the common human experience that we do this all the time. Hard determinism is a viewpoint that the human brain and the decisions arising from it are wholly determined by prior causes. In other words, the human brain is likened to a mechanism that operates within the confines of fixed processes, and it is this attribute that prohibits the possibility of free will.  In her book, Dirckx dismantles the philosophy of hard determinism in a beautifully concise section of her book (3) by asking three questions – is it internally consistent?, does it have explanatory power? and can it be lived? I do not wish to repeat her arguments here but just give a summary, with an emphasis on her third question. If I lived as a cause-and-effect machine, then any personally held belief is undermined – and this includes a belief in hard determinism itself, of course! Rather my precious conviction would just be the inevitable consequence of my neurons firing. If a determinist says we don’t have free will, and requests that I evaluate the proposition, I am unable to do this freely in the absence of free will. Effectively I would have no rationality – I would not be able to choose freely between concepts. Similarly, if you can’t make a free decision then there are other important consequences. I would effectively have no creativity, as I would be unable to choose freely between creative ideas. I would have no ability to love, as I would be unable to choose freely whether to embrace someone in that way. Perhaps the most significant issue is that I would have no personal culpability. In contemporary society, we are all considered to have moral responsibility, and are therefore accountable for our actions – I have a choice whether to do right or wrong. If this is not so then hard determinism threatens to unravel the cornerstone of moral responsibility and the need for justice. In other words, if you use the consequence of determinism as a defence in a court of law, the judge would most likely tell you, in no uncertain terms, to go away and rethink.  The scientific basis for saying that we do not have real freedom to make choices is the idea that the laws of physics allow us to predict the future based on knowledge of the current initial conditions. In other words, if we have knowledge of the current state of all the particles in your brain, then the laws lead us to a uniquely defined future state, therefore making freedom of choice an impossibility. However, this argument disregards the fact that physics is not yet complete. In fact, all of our laws of science – the mathematics we write down to make such predictions – are very much approximations to the reality, which is governed by the powerful agencies that enact what we call the laws of nature. For more detail, see the discussion in Chapter 2 of the book (4). Also, to make such claims when the path from fundamental physics to understanding mind and consciousness is completely uncharted, is, to me, the height of scientific hubris. Dirckx’s argument takes the discussion in the opposite direction, based upon the consequences if hard determinism reigns. Either way, the bottom line is that we live in a manner in which the decisions we make mean something and these are made by volitional people, and not by cause-and-effect machines. (1) Sharon Dirckx, Am I just my brain?, The Good Book Company, 2020 (2) The Holy Bible, Luke's Gospel, Chapter 11, verse 9 (NIV) (3) Reference (1), pp 85-88. (4) Graham Swinerd and John Bryant, From the Big Bang to Biology - where is God?, Kindle Direct Publishing, 2020, Section 2.4 Graham Swinerd Southampton August 2021 |

AuthorsJohn Bryant and Graham Swinerd comment on biology, physics and faith. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed