|

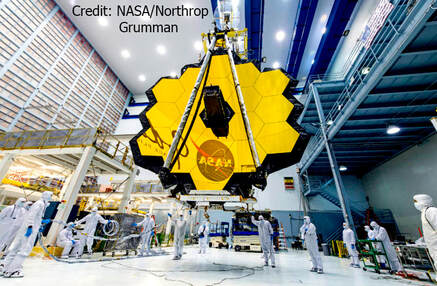

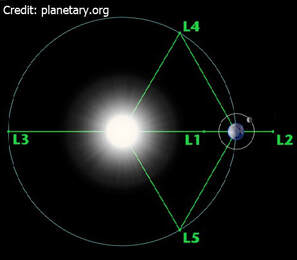

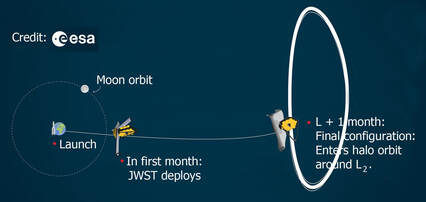

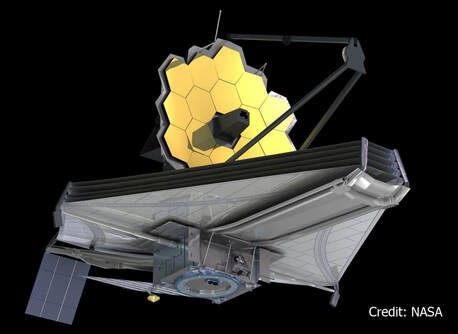

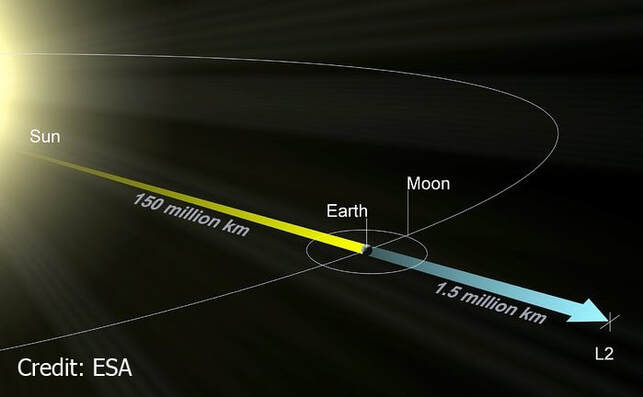

Graham writes … A new age of astronomy is about to begin, with the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). The new space observatory, named after the NASA administrator during the Apollo era, lifted off at 12.20 UT on Christmas Day 2021 atop a European Ariane 5 heavy-lift launch vehicle. A video of the launch and ascent (simulated) can be seen here, and another of the separation from the launch vehicle and power array deployment can be seen here. Both these videos are courtesy of Arianespace/NASA. Apologies once again to those of you who are looking out for the ‘New Physics? Part 2’ blog post, but the launch of the JWST is long-awaited and cannot be overlooked. If the new space telescope works as it supposed to, then it will most likely make history as did its predecessor, the iconic Hubble Space Telescope. This is a truly monumental event for the astronomy and cosmology communities.  At the time of writing, 6 January 2022 (~ launch + 12 days), the JWST is still on its way to its operational location – the Earth-Sun Lagrange point L2, which is about 1.5 million kilometres from Earth. It also has to deploy a significant number of mechanisms during its journey, so there are an awful lot of crossed fingers in the control centre and around the world. The operational configuration has a 6.5 metre aperture telescope and a sun shield about the size of a tennis court (~ 22 m x 12 m), and all this had to be stowed inside the launcher fairing of the Ariane 5. Consequently, there are around 140 release mechanisms that must perform perfectly to shape the final operational telescope. All this is going on while the JWST is in transit to L2, which will take about 30 days. An excellent video of the complete deployment process during the transfer, courtesy of NASA/Northrop Grumman, can be seen here. Once it arrives at the Lagrange point, it will enter its operational orbit, called a ‘halo orbit’, around this location. For more details about this exotic orbit and Lagrange points, see (1).  So, briefly, what is a Lagrange point and why is L2 a good place to operate an astronomical telescope? In any three-body system (for example, in this case, the Earth, Sun and spacecraft) there are in fact 5 Lagrange points, named in honour of the Italian-French mathematician Joseph Lagrange. The second Lagrange point L2 is about 1.5 million kilometres beyond the Earth’s orbit around the Sun (on a line joining the Sun, Earth and spacecraft) where the gravitational and rotational forces cancel to produce a place of equilibrium where the space observatory can be ‘parked’. This an ideal place for a space telescope, as the Earth only subtends an angle of about 0.5 degrees, so the sky viewing efficiency is excellent. The downside of this choice of orbit is that the observatory cannot be visited by astronauts to perform repairs or servicing. You may be aware that the Hubble Space Telescope was visited on five occasions by astronauts, as it was accessible in a low orbit near Earth. The table gives an outline of the main attributes of the observatory. Table: Summary of spacecraft characteristics Launch mass: 6,200 kg Overall dimensions: 22 m x 12 m (sun shield) Mirror aperture: 6.5 m (compared to 2.4 m for the HST) Maximum electrical power: 2 kW Planned operational lifetime: 5 to 10 years Operational temperature: -230 degrees (on the dark side of the sun shield)  Towards the end of this month (January 2022), the observatory should have completed the sequence of deployment mechanisms, and will enter its operational ‘halo orbit’ around L2 in its final configuration. While on station the sun shield will be directed towards the Sun and the subsystem module will be permanently located on the sunny side of the shield. This will enable the supporting subsystem elements, such as power, data handling and communications, to remain at a sensible temperature to ensure reliable operation. The telescope and associated payload elements will reside permanently on the dark side of the shield so that its temperature will be very low (see the last entry in the table). This thermal constraint indicates that the telescope is optimised to operate in the infrared (IR) part of the electromagnetic spectrum – that is, heat radiation (more about this below). The telescope needs to be at a very low temperature so that its own IR emissions do not interfere with the IR observations. The telescope’s mirror is comprised of 18 hexagonal elements manufactured from beryllium, with a thin coating of gold deposited on the reflective surface. This striking feature of a gold mirror is that it helps improve the mirror’s reflection of IR light. The composite hexagonal pattern of the main mirror has become something of a logo for the JWST project.  So why the emphasis on IR optimisation? This is, of course related to the science objectives of the observatory. It is hoped that the JWST will be able to see the ‘first light’ in the Universe, about 600 million years after the Big Bang, when the swirling dark clouds of hydrogen and helium began collapsing to form the first stars. It is also hoped that the processes involved in the origin of galaxies will be revealed. The ultra-violet and visible light emitted by the first luminous objects in the Universe is significantly red-shifted, due to cosmic expansion, into the IR part of the spectrum. Another objective is to study the birth of stars more locally, and the formation of embryonic planetary systems, which are usually obscured by the debris and dust associated with these events. Short wavelength visible light is appreciably scattered by dust. However, the longer wavelength IR radiation is less affected by this, allowing the telescope to observe these formative episodes.  Needless to say I am very excited by the prospect of all this, but we will have to wait till summer 2022 to see the first output from the JWST. Meanwhile, there is an awful lot of critical moments in the deployment and commissioning of the observatory. I am keeping everything crossed that this ambitious programme will all work out just fine! Graham Swinerd Southampton January 2022 (1) Graham Swinerd, How Spacecraft Fly, Springer, 2008, pp. 83-89.

2 Comments

Helen Williams

6/1/2022 09:10:57 pm

Presumably the angle subtended by the earth at L2 is small enough that the earth doesn't block out the sunlight needed to power the JWST? Or do the eccentricities in the various orbits mean that the sun isn't permanently in eclipse?

Reply

Graham

7/1/2022 11:47:09 am

Hi Helen - thanks for your comment. As you may know, L2 is a point of unstable equilibrium, so, rather than 'parking' the spacecraft there, they fly a large 'halo orbit' around L2. This can be done with the aid of a little station-keeping propellant. The plane of this orbit is roughly perpendicular to the Sun-Earth line, so the spacecraft is never in eclipse. The observatory is in a sense always in eclipse as it is hiding behind the sun shield. The 'sky-viewing efficiency' is good simply because the Earth/Sun does not obscure much of the sky. Compare this with Hubble, where the Earth obscures maybe 40% of the sky all the time, and inertially pointing observations can be interrupted for up to 30 minutes on every orbit. Hope this helps?

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsJohn Bryant and Graham Swinerd comment on biology, physics and faith. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed