The asteroid Dimorphos just moments before impact. The asteroid Dimorphos just moments before impact. Graham writes ... The DART spacecraft successfully impacted the asteroid Dimorphos in the early hours of this morning (UK time: 27 Sept), and I thought you might want to see what happened! Please click here to see a video courtesy of BBC News showing the moments just before impact. We will learn in the coming days whether the experiment was successful in changing Dimorphos's orbital speed, and consequently its orbit around Didymos. Graham Swinerd Southampton, UK September 2022

0 Comments

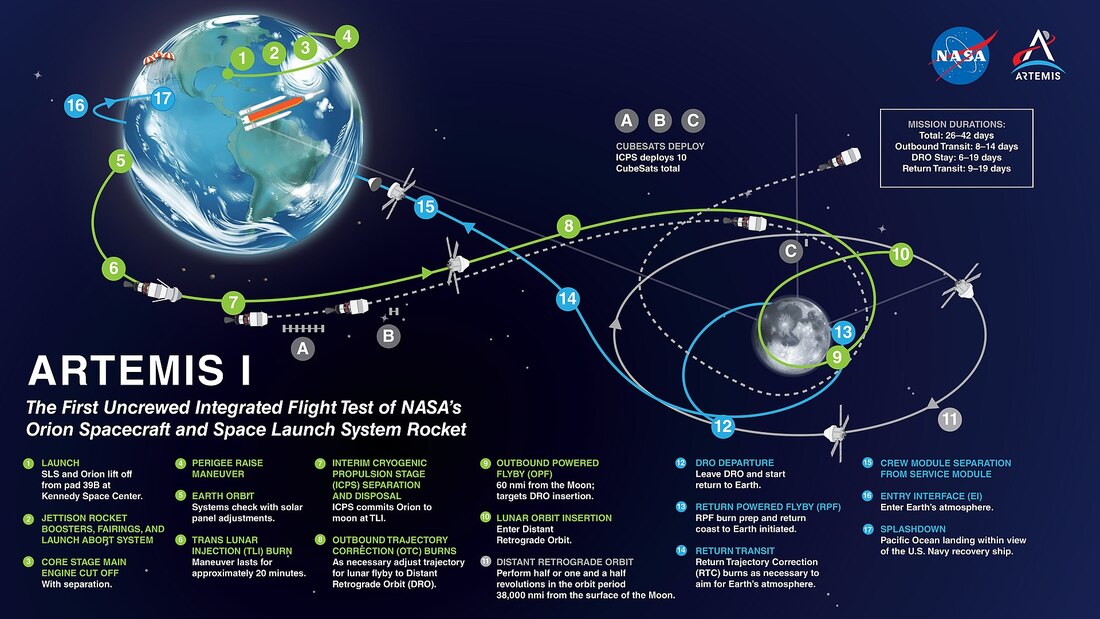

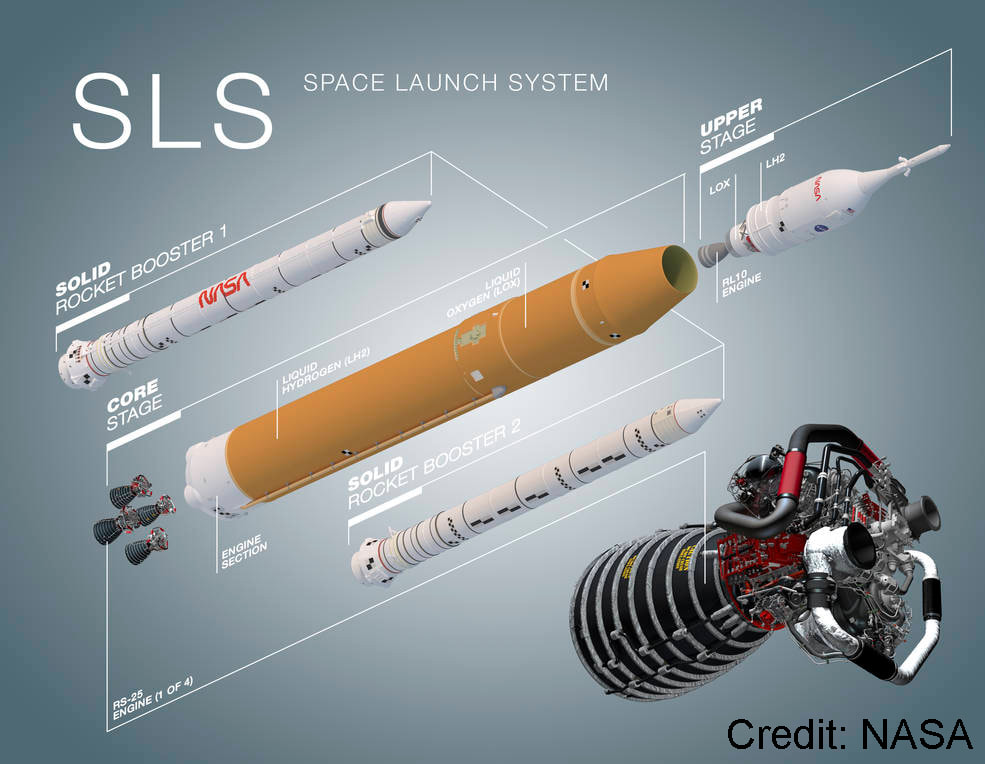

Graham writes … Alongside the impact event of the DART mission (see next blog post below), the other big happening this month is the proposed launch of the Artemis 1 mission – the first uncrewed test of the systems that are intended to return astronauts to the moon. The objectives of the Artemis programme are to establish a permanent crewed base on the moon, and to enable and test the necessary systems required for future missions beyond the moon. After the lack of ethnic diversity of the Apollo moon-walking astronauts, another unofficial aim is to take women and Black astronauts (and indeed Black women astronauts) to the lunar surface. NASA have already identified its ‘Artemis Team’ of 18 American candidates, and the involvement of other space agencies – ESA (European Space Agency), JAXA (Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency) and the CSA (Canadian Space Agency) – ensures a mix of other nationalities in future landing crews. The Artemis programme will also be supported by other initiatives, in particular the Lunar Gateway, which is a small, lunar-orbiting space station. This is expected to be in place by about 2027, and is intended to operate as a solar-powered communications node, a science laboratory and a short-term habitation module for astronauts. Unfortunately, the efforts to launch the Artemis 1 mission have not been successful so far. The first attempt took place on 29 August, but was abandoned because the temperature of one of the four main engines was indicated to be above the maximum allowable for launch. A second attempt, too, was aborted on 3 September due to a service arm fuel supply line leak. I have to admit that I tuned in on both occasions to NASA’s excellent live stream HD TV coverage with great excitement and anticipation. At my ‘great age’, I feel very impatient to see space exploration programmes up and running again – I just want them to get on with it! The next launch opportunity is 27 September, with a back-up on 2 October, and I shall be tuning again to the live coverage.  The Space Launch System (SLS) Artemis 1 waits on the launch pad, prior to the recent launch attempts. The Space Launch System (SLS) Artemis 1 waits on the launch pad, prior to the recent launch attempts. The Artemis 1 mission will be the first outing of the Orion spacecraft, which is planned to be of 38 days duration. Looking at the spacecraft configuration, at first sight it looks very much like the Apollo Command and Service modules, with the obvious difference being that Orion has deployable solar arrays for power generation. The power system on Apollo used fuel cells, which are effectively chemical engines that need an input of hydrogen and oxygen to produce electricity and water. This change facilitates the need for an additional water tank to supply the crew’s needs. However, the most significant difference is that the cone-shaped Orion crew module is significantly larger than the equivalent Apollo module, with about 30% more interior volume. Consequently, Orion missions will accommodate four crew members for a typical mission duration of about 21 days. Another significant difference is that the Orion Service module is European in design and manufacture. This cylindrically-shaped module is based upon ESA’s Automated Transfer Vehicle (ATV) (1) and provides the necessary services, such as power, propulsion, communications and life support & environmental control, required to keep the crew alive and to ensure a successful mission. The Orion system’s main engine, located at the rear end of the Service module, is a souped-up version of the Space Shuttle’s orbital maneuvering system engine, with a thrust of 33 kN. Mention of this prompts memory of a very unlikely encounter a while ago with a NASA engineer who worked on the development of this Shuttle propulsion technology for the Orion spacecraft. In 2011, my wife and I had a lovely holiday break walking the coastal path of Pembrokeshire, South Wales, and on this particular day I was wearing my NASA baseball cap. Coming the other way was a couple, and the gentleman was wearing a similar cap. We started to converse, and found that we shared a professional interest in space technology. He told me about his work on the Orion programme, and I told him about the upcoming, and ground-breaking ESA comet lander mission, called Rosetta, which he’d known nothing about. A remarkable meeting, in a beautiful place in lovely weather, which would not have happened if I hadn’t been wearing my NASA cap to protect me from the sun!  Anyway, back to Artemis. One thing that surprised me about the new Space Launch System (SLS) was that NASA has returned to the Saturn V philosophy used on the Apollo programme launches. This is along the lines of stacking everything– the crew and service modules, plus the lunar lander module – all on one rocket. The reason for my surprised reaction is the intention to put people on top of such a large vehicle. The energy contained within its chemical propellants is equivalent to that of a small atom bomb. Despite the existence of a dedicated launch escape system, this seems to me to be an unnecessary risk. The Agency got away with it on the 13 Saturn V launches during the Apollo era, but why take the risk now? There is in fact a better – safer and more flexible – way of doing this, which was proposed during the Constellation ‘return to the moon’ programme in around 2004. At that time, the imminent retirement of the Space Shuttle in 2011 dictated a rethink of the American space programme by the then-Bush administration. There had been a realization – a hard lesson learned – that complex spacecraft like the space shuttle are dangerous. Seven flight crew were killed on launch in the Challenger accident in 1986, and another seven died when the shuttle Columbia broke up on reentry in 2003. In light of this, a new approach to launching people was recommended in the Constellation programme. In this proposal, to launch the crewed Orion spacecraft a new man-rated launch vehicle was developed called Ares 1 using existing components derived from Shuttle and Apollo hardware. This new vehicle was small and very simple, with a genuine crew escape system, with the result that it would be very reliable and safer for future crew launches to Earth orbit and for lunar missions. The hardware for the mission, for example the lunar lander, equipment required for developing or supplying a moon base and a propulsion stage, would be launched separately on an uncrewed, heavy-lift launch vehicle, called Ares 5. Subsequently, the crewed vehicle and the mission payload vehicle would rendezvous in orbit, before departure for the moon. Although the Ares 1 and 5 launch vehicles were to be developed primarily for lunar missions, NASA envisaged a wider role for them involving crewed space missions to destinations other than the moon. A test flight of Ares 1 was performed, designated Ares 1-X, but nevertheless the Constellation programme was cancelled by the incoming Obama administration in 2010. With the retirement of the Shuttle in 2011, this left the US Space programme in the remarkable position of being principal operator of the International Space Station, but without any means for US astronauts to reach it in Earth orbit, other than by ‘hitching a ride’ on Russian crewed vehicles. For more detail about the Constellation programme, please see (2). You might ask, why am I discussing return-to-the-moon space programmes in a blog to do with science and faith? Well firstly, with my physicist’s hat on, the Artemis launch is a truly major event in the realm of the physical sciences. But then secondly, and perhaps less obviously, the spiritual or religious experiences of astronauts are worth reflecting upon. And this is not limited to moon-walking astronauts, but can be extended to those who have spent considerable time in Earth-orbiting space stations.

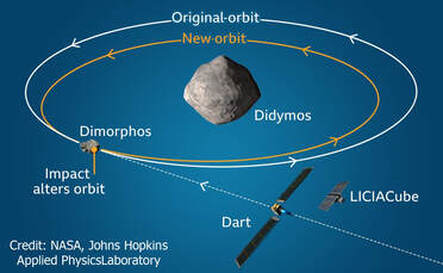

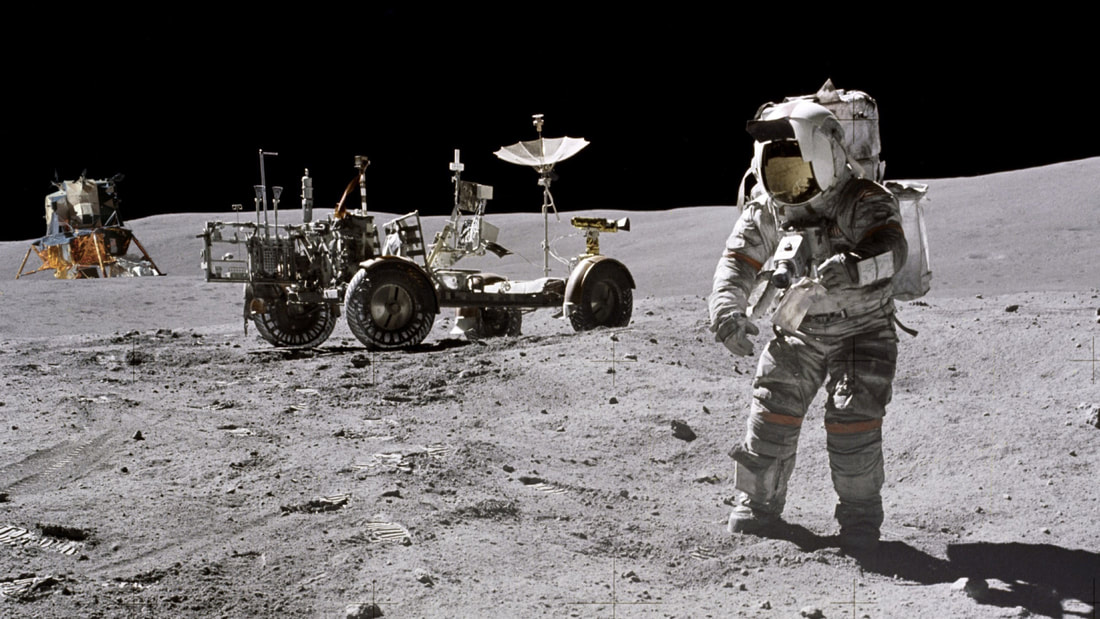

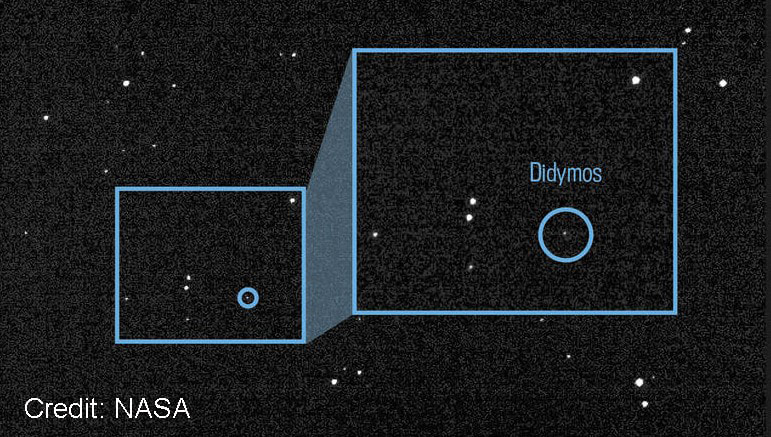

It is no secret that several of the Apollo astronauts were practicing Christians. Perhaps the most overt evidence of this is the remarkable occasion when the three astronauts aboard the Apollo 8 lunar-orbiting mission, Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and William Anders, read the first 10 verses of the first chapter of Genesis on Christmas Eve in 1968 (3). Then, on the occasion of the first historic landing mission Apollo 11, shortly before the lunar surface walk lunar module pilot Buzz Aldrin addressed the people of Earth: “I would like to request a few moments of silence … and to invite each person listening in, wherever and whomever they may be, to pause for a moment and contemplate the events of the past few hours, and to give thanks in his or her own way”. He then celebrated communion (the taking of bread and wine in remembrance of the sacrifice of Jesus Christ). Also, the commander of the final landing mission Apollo 17, Eugene Cernan, made no bones about his faith and was awed by what he believed was God’s amazing creation while on the lunar surface. He later commented: “There is too much purpose, too much logic [in what we see about us]. It was too beautiful to happen by accident. There has to be somebody bigger than you, and bigger than me …” (4). Other moon-walking astronauts related spiritual experiences induced by their journey to the lunar surface. Notably Apollo 14 astronaut Edgar Mitchell commented that “something happens to you out there”, and Apollo 15 astronaut Jim Irwin quoted the Bible during his lunar walk (5), and felt “touched by grace”. I guess it’s not too surprising that devout spacefarers would relate how their lunar mission influenced and strengthened their faith. Perhaps what is more remarkable is that many experienced a spiritual dimension in their lunar visit, simply by virtue of the ‘cosmic awe’ they encountered. It would seem that space in some way connects us to the divine. Graham Swinerd Southampton, UK September 2022 (1) The ATV was used for supply missions to the International Space Station up to 2015. (2) Graham Swinerd, How Spacecraft Fly: Spaceflight without Formulae, Springer, 2008, pp. 222-225. (3) Graham Swinerd & John Bryant, From the Big Bang to Biology: where is God? KDP publishing, 2020, p. 45. (4) Ibid., p 208. (5) Holy Bible (NIV) Psalm 121:1 “I lift my eyes to the mountains – where does my help come from?” Graham writes … This blog post is a very brief heads-up about the upcoming impact event, which is the centre piece of NASA’s DART (Double Asteroid Redirection Test) mission. This will occur, as planned, on 26 September. For more detail about the mission, please refer to the December 2021 blog post, which includes a video discussion between John and myself.  Analysis of the impact dynamics will be acquired by examination of the changes in Dimorphos's orbit. Analysis of the impact dynamics will be acquired by examination of the changes in Dimorphos's orbit. Essentially, this is the first spacecraft mission devoted to planetary defense science. In particular, the objective is to study the effectiveness of the kinetic impactor technique in changing the orbit of an asteroid to prevent a future, devastating asteroid collision with our home planet. Although such collisions with a large asteroid (greater than, say, 1 kilometre in diameter) are very rare, nevertheless we know that such events are inevitable in the long term. For this test, the target asteroid is a 160 metre diameter object called Dimorphos, which itself is in orbit around a larger asteroid (780 metres across) called Didymos. It’s worth pointing out that neither object poses an impact threat to the Earth! The idea is that the spacecraft will impact Dimorphos, causing a tiny change in its orbital speed. Although this change is very difficult to measure directly, the magnitude of the change can be calibrated very precisely by observing long-term changes in Dimorphos’s orbit around Didymos. In particular, the resulting cumulative change in its orbit period over many orbit revolutions can be observed subsequently using Earth-based telescopes. Watch out for media coverage of this historic event in the coming days, and for information about what DART tells us about planetary defense in slower time. Graham Swinerd Southampton, UK September 2022 |

AuthorsJohn Bryant and Graham Swinerd comment on biology, physics and faith. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed