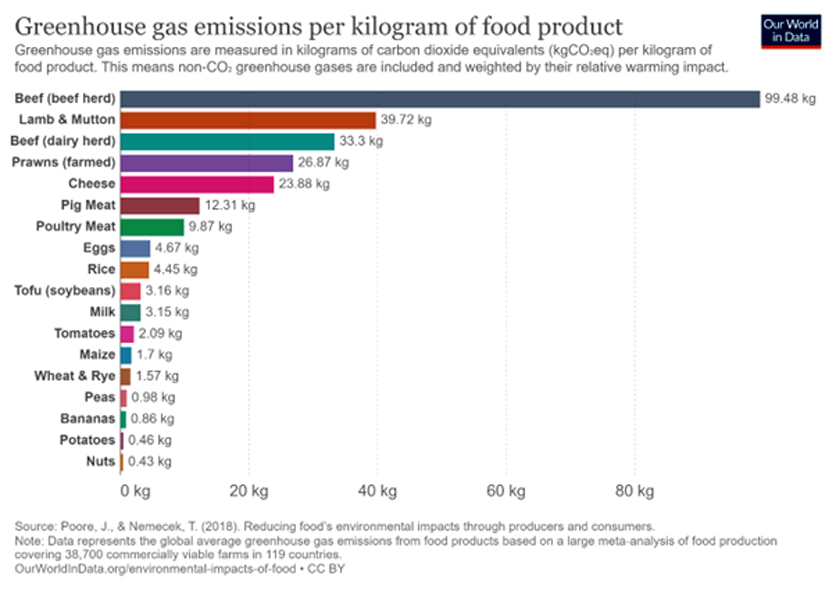

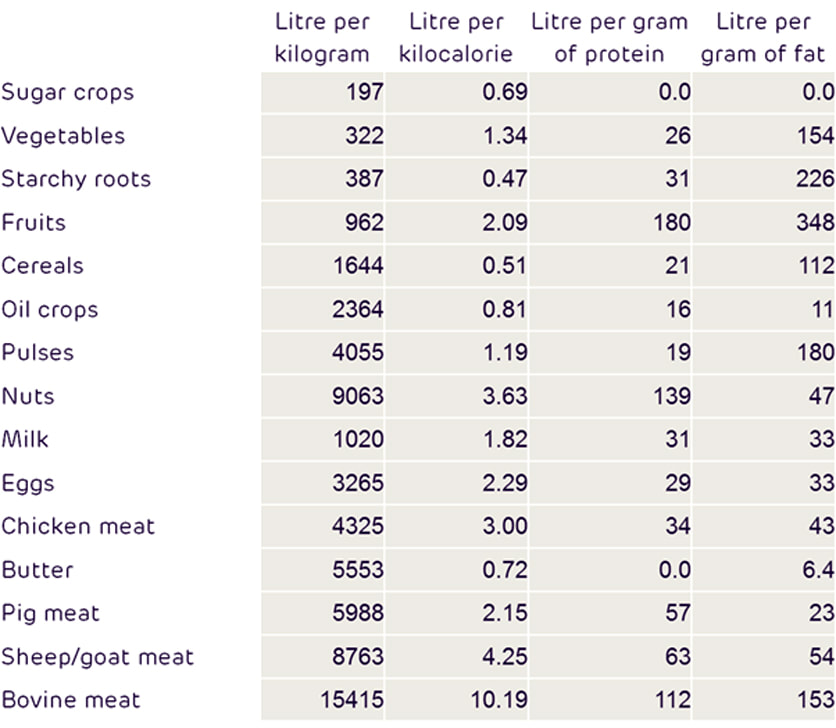

Credit: John Bryant Credit: John Bryant John writes … Plants and our planet. My PhD supervisor, Dr (later Professor) Tom ap Rees often quoted the phrase which I have used as the title of this blog. It is actually part of a verse from the Bible: 1 Peter, chapter 1, v 24: All flesh is grass and all its glory like the flowers of the field; the grass withers and the flowers fall … . The verse refers to the transience of human life and my supervisor had doubtless heard his father, a church minister, quote it at various times. However, Tom ap Rees’s use of it in our lab conversations took us in a very different direction. He was referring to our total dependence on plants, which was one of his major motivations for doing research on how plant cells control their metabolism and which has driven my research on plant genes and DNA.  Jubilee Oak Tree. Credit: John Bryant. Jubilee Oak Tree. Credit: John Bryant. Let us look at this a little more closely. I am very fond of saying that without plants, we would not be here. This may seem rather sensationalist but it is true. It is a statement of the dependence of all animals (and indeed of many other types of organism) on green plants for their very existence. We see hints of a partial understanding of this in the media as they debate ways of mitigating climate change. Planting trees is correctly lauded as a means of capturing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere while at the same time releasing oxygen. Further, these two features have featured strongly in the evolution of life on Earth, as we describe in Chapter 5 of the book: the first occurrence of photosynthesis in simple micro-organisms (similar to modern blue-green bacteria) about 2.8 billion years ago and the invasion of dry land by green plants about 472 million years ago had major effects which have led to the development of the biosphere as we know it today. However, what is often not emphasised enough in our discussions is that the process which takes in carbon dioxide and gives out oxygen, namely photosynthesis, uses energy from sunlight to drive the synthesis of simple sugars. This process requires light-absorbing pigments, mainly the chlorophylls which are green because they absorb light in the red and blue regions of the spectrum. The mixture of light wavelengths which are not absorbed gives us green. Green plants are thus our planet’s primary producers. This ability of plants to ‘feed themselves’ (autotrophy) is essential for the life of all non-autotrophic organisms, namely animals of all kinds, fungi and some micro-organisms. Non-autotrophic organisms such as ourselves are thus directly or indirectly dependent on green plants for their nutrition. We eat plants or we eat organisms that themselves eat plants. Thus, I repeat ‘Without green plants we would not be here’. ‘All flesh is grass’.  Credit: John Bryant Credit: John Bryant Plants and population. I now want to look at this in the context of feeding a hungry world at a time of changing climate (1). Current estimates from charities such as TEAR Fund, Christian Aid and OXFAM indicate that about 800 million people are undernourished. In 2020, 9 million people actually died from malnutrition. This compares to the total number of deaths from malaria, HIV, TB and flu combined, of 3.17 million in the same year. Poverty is undoubtedly one of the main drivers of this situation: food needs to be more readily and cheaply available but food production also needs to be increased. Further, current projections suggest that the global population will increase to about 9 billion by 2050, an increase of about 1.05 billion on the current figure (2), with the vast majority of the increase occurring in low and middle-income countries (LMICs). At the same time, agricultural land is being lost to the effects of climate change and there is also some loss in order to house the increasing population. The situation has been described as a perfect storm. I am going to focus specifically on the tension between two imperatives that I described in the previous paragraph, namely care for planet Earth and care for its human inhabitants. What are the environmental ‘costs’ we incur as we produce enough food for a population which is already fast approaching 8 billion and which is set to reach 9 billion within 30 years? The table below sets out one of those costs, namely the production of greenhouse gases. It is immediately and obviously apparent that farming of animals for food is far more ‘expensive’ than farming of crops. For example, beef production produces more than 50 times the quantity of greenhouse gases per kilogram of food than does wheat production. We need to note in passing that this way of expressing the data (‘per kilogram of food product’) places milk (whether from cows, sheep or goats) in an anomalously low position on the chart because 1 kg of milk is largely water. We get a better idea of the costs of producing the main nutrients in milk – protein and lipid - by looking at cheese production. I now want to look at two other aspects of the costs of food production, land use and water use. These must both come into our consideration as we attempt to balance the tensions involved in ‘feeding the nine billion’. Firstly, about 75% of the world’s agricultural land is used for animal production. This figure includes land that is used to grow crops for animal feed. Crops for direct human consumption occupy the remaining 25%. However, the yield of food obtained from just one quarter of the total agricultural land exceeds that obtained from the three quarters devoted to farming animals. Indeed, depending on the particular animal under consideration, the average protein yield per hectare of crop land is six times that of land devoted to animal husbandry. Secondly, there is water usage which, like land use, shows a huge difference between plant- and animal-based food production, as is shown in the following table, taken from Mekonnen and Hoekstra (2010). Overall then, the data from agricultural science and biogeography indicate that crop growth is ‘better’ for the planet than animal farming and that concentrating more on crops than on animals is likely to be the better route to feeding the burgeoning population. However, I am not forgetting that some land is better suited to animals than to crops, as discussed by Isabella Tree in her book Wilding (3). Nor am I trying to dictate that we should all move to a plant-based diet: in the rich industrialised nations of the world, we are privileged that this is a matter of personal choice. Nevertheless, it is clear that there must be extensive focus on plant science - genetics, molecular biology, biochemistry and physiology - over the next 20 years, both in respect of mitigating climate change and in respect of global food production. That science will be the subject of a future blog.

John Bryant Topsham, Devon June 2022

0 Comments

|

AuthorsJohn Bryant and Graham Swinerd comment on biology, physics and faith. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed