|

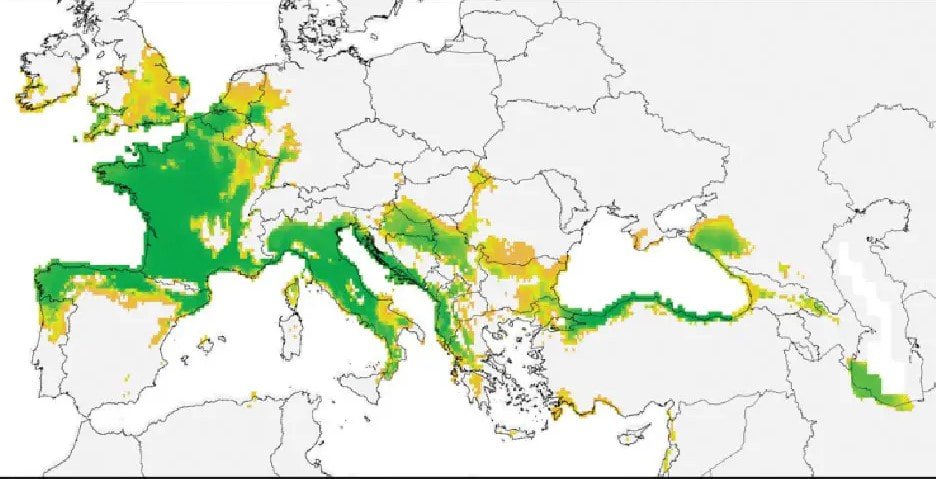

John writes … Introduction. Earlier in the month, I was interested to note that both Nature, the UK’s leading science research journal and New Scientist, the UK’s leading popular science magazine, drew attention to an article about invasive species that had appeared in The New York Times (1). What do we mean by invasion? To start to answer this question I go back to the early and middle years of the 20th century and tell the story of three species of bird. The first is the Collared Dove. This originated in India but over several millennia had slowly spread west and became well established in Turkey and SE Europe. Then, in the early 1930s it started to spread north and west, reaching The Netherlands in 1947 and first breeding in Britain (in Norfolk) in 1956. From there it went on to rapidly colonise the whole country. By 1976 it was breeding in every county in the UK, including the Outer Hebrides and Shetland and is now a familiar inhabitant of parks and gardens.  Fulmar. Fulmar. The second bird is a sea bird, the Fulmar, which breeds on maritime cliffs. It is now widely distributed in the north Atlantic and sub-arctic regions but until the late 19th century, its only breeding colonies were in Iceland and on St Kilda, a remote archipelago of small islands 64 km west of the Outer Hebrides. However, in the 1870s, their range started to expand outwards from St Kilda and from Iceland. Fulmars first bred in Shetland in 1878 and then slowly moved south via Orkney, down both the east and west coasts of Britain. They first bred at Bempton in Yorkshire in 1922 and at Weybourne in north Norfolk in 1947. The range extension included Ireland and Norway in Europe and westwards to Greenland and Canada. In Britain, the west coast and east coast expansions completed the circling of the British mainland by meeting on the south coast in the late 1970s. Since then, southern expansion has continued into northern France.  Little Egret. Little Egret. The third species is the Little Egret, a marshland bird in the Heron family. Until the 1950s, this was regarded as a species of southern Europe and north Africa which was very occasionally seen in Britain. However, it then began to extend its range north, breeding in southern Brittany for the first time in 1960 and in Normandy in 1993. By this time, it was seen more and more frequently along the coasts of southern Britain, especially in autumn (2) and the first recorded breeding was in Dorset in 1996 (and in Ireland in 1997). Little Egrets now breed all over lowland Britain and Ireland and disperse further north in autumn and winter. These three birds give us clear pictures of ecological invasions. They have extended their range, become established in new areas and are now ‘part of the scenery’. In these cases, the invasions have not been harmful or detrimental to the newly occupied areas nor have any species already there been harmed or displaced. The invaders have been able to exploit previously under-exploited ecological niches and in doing so have increased the level of biodiversity in their new territories. The ‘balance of nature’ is thus a dynamic balance. Increases and reductions in the areas occupied by species have occurred and continue to do so. Such changes are usually the result of changes in the physical environment or of changes in the biological environment that result from physical changes. At one end of the scale there have been very large physical changes. Consider for example the series of glacial and inter-glacial periods that have been occurring over the past 2.6 million years during the Quaternary Ice Age. The last glacial period ended ‘only’ about 11,700 years ago and during the current inter-glacial period there have been several less dramatic and more localised fluctuations in climate which had some effect on the distributions of living organisms (although obviously not as dramatic as those shifts resulting from alternating glacial and inter-glacial periods). Having said all this, I need to add that there is no consensus about the reasons for the three dramatic extensions to breeding range that I described above. However, some more recent and currently less dramatic changes in the ranges and/or in migratory behaviour of some bird species are thought to be responses to climate change.  Rabbit. Rabbit. Introductions and invasions. The natural invasions described above contrast markedly with the situation described in the New York Times feature: the author writes that ‘over the last few centuries’, humans have deliberately or accidentally introduced 37,000 species to areas outside their natural ranges. Nearly 10% of these are considered harmful and it is these harmful introduced species that are termed ‘invasive’. But actually, human-caused animal introductions go back further than the last few centuries. For example, rabbits were introduced to Britain by the Romans, probably from Spain and there is evidence of their being used both as ‘ornamental’ pets and as food. It is not clear when the species became established in the wild in Britain although the best-supported view is that this started to occur in the 13th century. What is clear is that rabbits are now found throughout Britain, with the rather curious exceptions of Rùm in the Inner Hebrides and the Isles of Scilly. The introduction of rabbits to Britain is probably representative of a slow trickle of introductions as human populations moved across Europe but the rate surely started to increase as the world was explored, colonised and exploited by various European nations. The rate increased still further with, for example, the widespread collection of exotic plants and animals which gathered pace in the 18th and 19th centuries. And alongside the carefully garnered specimens for zoo or garden, there were doubtless species that in one way or another came along for the ride, just as in previous centuries, European explorers and colonisers accidentally took rats into lands where they had never previously occurred. Further, as international trade and travel has increased since Victorian times – and indeed is still increasing – so the possibility of introductions has also increased and is still increasing (current rate is about 200 per year). Even so, the number of 37,000, quoted above, seems difficult to comprehend, although I do not any way doubt the reliability of the data (provided by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, IPBES). Further, as mentioned above, nearly 10% of these introduced species cause harm of some sort in their new environment. This may be harm to nature because of negative interactions with native species or because of damage to the environment; it may be damage to agriculture or other aspects of food systems or it may be harm to human health. Taken together, it is estimated that these harmful introductions ‘are causing more than $423 billion in estimated losses to the global economy every year’ (3). Some examples of harmful introductions. It is clearly not possible to discuss all 3500+ species whose introductions have been harmful so I am going to present a selection, mainly relevant to Britain, that give examples of different levels and types of harm. Plants. Rhododendron. There are several species of rhododendron but only one, Rhododendron ponticum (Common Rhododendron) is considered invasive. Its native distribution is bi-modal with one population around the Black Sea and the other on the Iberian peninsula. These are actually fragments of its much wider distribution, including the British Isles, prior to the last glaciation. It has thus failed to re-colonise its former range after the retreat of the ice and our post-glacial eco-systems have developed without it. In the 1760s it was deliberately introduced to Britain and in the late 18th and early 19th centuries was widely sold by the growing nursery trade both as a hardy ornamental shrub and as cover for game birds. However, it is now regarded as an invasive species: it has covered wide areas in the western highlands of Scotland, parts of Wales and in heathlands of southern England. In all these regions, rhododendrons can quickly and effectively blanket wide areas, to the exclusion of most other plant species and to the detriment of general biodiversity. Winter heliotrope.  Winter Heliotrope. Winter Heliotrope. This plant is also listed as an invasive non-native species but its invasiveness is more localised than that of rhododendron. Its native range is the Mediterranean region. It was introduced into Britain as an ornamental garden plant in 1806 and was valued for its winter flowering (December to March) and the fragrance of the flowers. Only male plants were introduced and thus the species cannot produce seeds in this country. However, it spreads via vigorous underground rhizomes and can grow from fragments of those rhizomes. Nevertheless, it is not clear how this species became established in the wild, first recorded in Middlesex in 1835: were some unwanted plants/rhizome fragments thrown out? Once established, it quickly covers the ground with its large leaves smothering or shading out nearly all other species. In the two locations that I know where it is growing in the wild, the area covered is increasing year by year. Interestingly, at least one national park authority has a specific policy to control and/or exterminate winter heliotrope while the Royal Horticultural Society has published advice about controlling it when it is grown as a garden plant. Himalayan Balsam (also known in some cultures as Kiss-me-on-the mountain).  Himalayan Balsam. Himalayan Balsam. As the name implies this plant originates from the Himalayan region of Asia. It was introduced to Britain in 1839 by Dr John Forbes Royle, Professor of Medicine at Kings College, London (who also introduced giant hogweed and Japanese knotweed!). The balsam was promoted as an easy-to-cultivate garden plant with attractive and very fragrant flowers. In common with other members of the balsam family, including ‘Busy Lizzie’, widely grown as a summer bedding plant, Himalayan Balsam has explosive seed pods which can scatter seeds several metres from the parent plant. It is no surprise then that the plant became established in the wild and by 1850 was already spreading along river-banks in several parts of England. Its vigorous growth out-competes other plants while its heady scent and abundant nectar production may be so attractive to pollinators that other species are ignored. Further, the explosive seed distribution means that spread has been quite rapid. It now occurs across most of the UK and in addition to its out-competing other species, it is also regarded as an agent of river-bank erosion. Invertebrate animals. Asian Hornet. This species has been very much in the news this and last year. The main concern is that it is a serious predator of bees, including honey bees, so serious in fact that relatively small numbers of hornets can make serious inroads into the population of an apiary, even wiping it out completely in the worst cases. So why would anyone want to introduce this species? Answer: they wouldn’t. Asian hornets arrived in France by accident in 2004, in boxes of pottery imported from China. From there it has spread to all the countries that have a border with France. Indeed, as the map at the head of this article shows, ideal conditions exist for the Asian hornet across much of Europe. It was first noted in Britain in 2016 and since then there have been 58 sightings, nearly all in southern England (4); 53 of the sightings have included nests, all of which have been destroyed. The highest number of sightings has been in this year, with 35 up to the first week of September. By contrast, there is no evidence that Asian hornets are established in Ireland. Box-tree moth.  Box-Tree Caterpillar and Moth. Box-Tree Caterpillar and Moth. Those who follow me on Facebook or X (formerly Twitter) will know of my encounters with the Box-tree Moth. There has been a major outbreak this year in the Exeter area, with box hedges and bushes being almost completely defoliated by the moth’s caterpillars. At the time of writing, the adults are the most frequently sighted moth species in our area. Box-tree Moth is native to China, Japan, Korea, India, far-east Russia and Taiwan; there are several natural predators in these regions; these keep the moth in check and so damage to box bushes and trees is also kept in check. However, in Europe there are no natural predators and thus a ‘good’ year for the moth can be a very bad year for box. Looking at the pattern of colonisation in Europe it appears that it has been introduced more than once, almost certainly arriving on box plants imported from its native area, as is proposed for its arrival in Britain in 2007 (5). Like the Asian hornet then, its introduction was accidental but it has left us with a significant ecological problem to deal with.  Cane toad. Credit: Froggydarb, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0. Cane toad. Credit: Froggydarb, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0. Vertebrate animals. Cane toad. The cane toad is surely the best-known example of deliberate introductions that have gone very badly wrong. As we discuss this, we need to dispel from our minds any notions of toads based on the familiar common toad. Cane toads are, as toads go, enormous, weighing up to 13 kg; they also secrete toxins so that their skin is poisonous to many animals; the tadpoles are also very toxic. Cane toads are native to Central America and parts of South America and have also been introduced to a several islands in the Caribbean. It is a predator of insect pests that feed on and damage sugar cane. It was this feature that led in 1936 to its introduction into Queensland, Australia where it was hoped that it would offer some degree of protection to the sugar cane crop. However, as one commentator stated, ‘The toads failed at controlling insects, but they turned out to be remarkably successful at reproducing and spreading themselves.’ They have spread from Queensland to other Australian states; they have no predators in Australia (in their native regions, predators have evolved that can deal with the toxins). They eat almost anything which means that they are a threat to several small animal species firstly because they compete for food and secondly because the toads eat those animals themselves. The population of cane toads in Australia is now estimated at 200 million and growing and they are regarded as one of the worst invasive species in the world. Grey Squirrel (also known as the Eastern Grey Squirrel).  Grey squirrel. Grey squirrel. Many of us enjoy seeing grey squirrels; they are cute, they are inventive and clever and they often amuse us. But wait a moment – and aiming now specifically at British readers of this blog – these agile mammals that we like to see are not the native squirrels of the British Isles. The native squirrel is the red squirrel which has, over many parts of the UK, been displaced by its larger, more aggressive relative. Grey squirrels imported from the USA were introduced into the grounds of stately homes and large parks from around 1826 right through to 1929. It was from these introduced populations that the grey squirrel spread into all English counties – although it was not until the mid-1980s that they reached Cumbria and the most distant parts of Cornwall. This is an invasion that has been happening during the lifetime of many of our readers. But what is the problem? The problem is that in expanding its range, the grey squirrel has displaced the native red squirrel which is now confined to the margins of its previous range. I need to say that there are several factors that have contributed to this decline but that the grey squirrel is certainly a major one. The grey is more aggressive than the red which is important in that they often compete for the same foods and the grey also seems to be more fertile. Further, the grey squirrel carries a virus which is lethal to the red squirrel. Thus, overall, the introduction of a species to add interest to a stately home or to a large area of parkland has had a significant effect on ecosystems. Final comment.

As I stated at the beginning, ecosystems are in a state of dynamic balance with some degree of self-regulation. We need to think about this before taking any action that may interfere with that dynamic balance. And also, in view of the ways in which Asian hornet and Box-tree Moths arrived, check incoming packages very carefully! John Bryant Topsham, Devon September 2023 All images are credited to John Bryant unless stated otherwise. (1) Manuela Andrioni, Invasive Species Are Costing the Global Economy Billions, Study Finds, The New York Times, 4 September 2023. (2) On one autumn afternoon in the early 1990s I counted 34 in a flock on the Exe estuary marshes. (3) Data from IPBES: IPBES Invasive Alien Species Assessment: Summary for Policymakers | Zenodo. (4) Asian hornet sightings recorded since 2016 - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk). (5) The Box-Tree Moth Cydalima Perspectalis (2019) (rhs.org.uk).

0 Comments

|

AuthorsJohn Bryant and Graham Swinerd comment on biology, physics and faith. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed